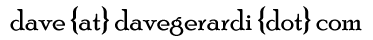

That Darn Punk

This appeared in a movie mag way back before Harvey Weinstein left Disney. Independent film had lost its bloom because it had been taken over by major studios and big time execs. This article covers a new economic model for indie filmmaking. I thought maybe I could coin a new term, DIY filmmaking. Like 8-track tapes, it didn't stick.

HED: Kung Fu Fighting

DEK: The Vandals' Joe Escalante is spearheading a new form of do-it-yourself filmmaking.

by Dave Gerardi

If you believe everything Harvey Weinstein says, Disney-owned Miramax is still an indie film studio. That may wash for the Sundance judges but not for those who once equated indie filmmaking with the iconoclasm of punk rock.

If the term 'indie film' has lost its original meaning, maybe do-it-yourself (DIY) film ought to be the new term. Joe Escalante, bassist for the venerable Los Angelino punk band The Vandals and head of Kung Fu Records, is spearheading a straight-to-video distribution concept steeped in the punk ethos that launched such successful record labels as Dischord (Fugazi, Minor Threat), Epitaph (Bad Religion), Fat Wreck Chords (NOFX).

The formula behind Escalante's That Darn Punk may sound antithetical. No big name stars. No festivals. No theatrical distribution. Yet advance orders for the soundtrack alone covered the cost of the film's production four times over.

In 1996, Kung Fu Records released a soundtrack of punk music for Glory Daze (starring Ben Affleck). The soundtrack sold 10,000 units before the film limped into art house theaters a year later. "We thought it'd be easier to distro a record as opposed to a film," says Escalante, now 38. Escalante and friend Jeff Richardson hooked up to put together a $21,000 full-length 16mm film. The involvement of The Vandals and Escalante's punk contacts became the crux of the project.

"No one would be interested in a small film with no stars," says Richardson. "I said, 'Wouldn't it be cool to make a film like you guys make these punk albums?'"

The soundtrack, which features The Vandals, Rancid, Pennywise and other punk stalwarts, leveraged the support of the typically loyal punk following built by Kung Fu Records and other California-based labels and bands. Kung Fu put up the money for the film and released it day and date with the soundtrack. There's "$100,000 worth of music in there--at least," says Escalante, whose long-standing relationships with the bands allowed him to give them points on the soundtrack in lieu of an up-front fee.

Escalante was working as a production assistant on an HBO series in 1992 while waiting for the results on his bar exam (he's also a lawyer) when he met Richardson. Escalante convinced Richardson to incorporate more of a punk theme into his script so the film would appeal to the same group that would buy the soundtrack. In return, Kung Fu financed the picture and distributed it using The Vandals' fan base.

To be sure, the soundtrack drives the film. "Nobody else will make something we (punk rockers) want to see," Escalante says. The music, Richardson adds, didn't interfere too much: "It made sense to open it in a punk club and to do a 'making of the video' scene, but not the sunset."

Escalante laughs, "From the beginning, I kept saying, 'We have to put more punk rock music here.'" The sunset scene to which they refer has Escalante (who stars in addition to producing the film) walking to L.A. in the desert with a sunset in the background. It's a pretty shot but also a long one. Its length is due not to any cinematic concerns, but to provide a slot for No Motiv's "Only You." It's one of several pacing problems throughout the film. "I thought about cutting the first half-hour," Richardson explains, talking about conventional cinematic devices That Darn Punk eschews. The narrative structure is a bit jumpy and the ending tacked-on, but the protagonist's crisis is real. He has skirted his way through much of his life and now has to face up to it.

Other production problems were more typical of a low budget feature. "Sometimes, we would pay $50 an hour to shoot in a restaurant or store, and then the real owner showed up," Escalante remembers. Fatigue was another factor. They shot on nights and weekends, and director Richardson did triple duty as camera operator and director of photography. Without a regular crew, he occasionally taped the microphone boom to a C-stand.

"We shot one scene in an alley. When we came back, it was a construction site," Richardson says, but adds the biggest problem was Escalante's hair. Throughout the film, he has short brown hair dyed blonde. Unfortunately, the dye job wasn't a recent one: He had brown roots. "It was a big pain in the ass," Richardson grumbles. Every few months, they had to cut it, dye it blonde and wait for it to grow out again.

A key to Escalante and Richardson's distribution plan is their end run around conventional channels. They did it through Kung Fu Records and avoided the time-honored festival route entirely. "You would never take a punk record to a festival and play for adults," explains Escalante. Why, he asks, would you do it for a punk film?

For Richardson, the whole independent film scene has changed, "Sundance used to be the place for the indie. It's like the major labels signing the Butthole Surfers. The fringe becomes 'classic.'"

That Darn Punk will make millionaires of nobody, but Escalante's reliance on small budgets and his punk fan base have allowed him to complete his next project, Selwyn's Nuts, his directorial debut which comes out this summer. It too will be buoyed by a punk soundtrack.

Can Escalante's films stand on their own? When the film and soundtrack are merchandised side by side, he smiles, "the film outsells (the soundtrack) five to one."